When I first came home, I was released to the Male Community Reentry Program (MCRP). So, I was wearing an ankle monitor for a year and going to school. In the circles I participated in we had a saying that my people die for a lack of knowledge. So, when I was in MCRP, I tried to encourage everyone to go to school, and I would share that I was taking classes at City College.

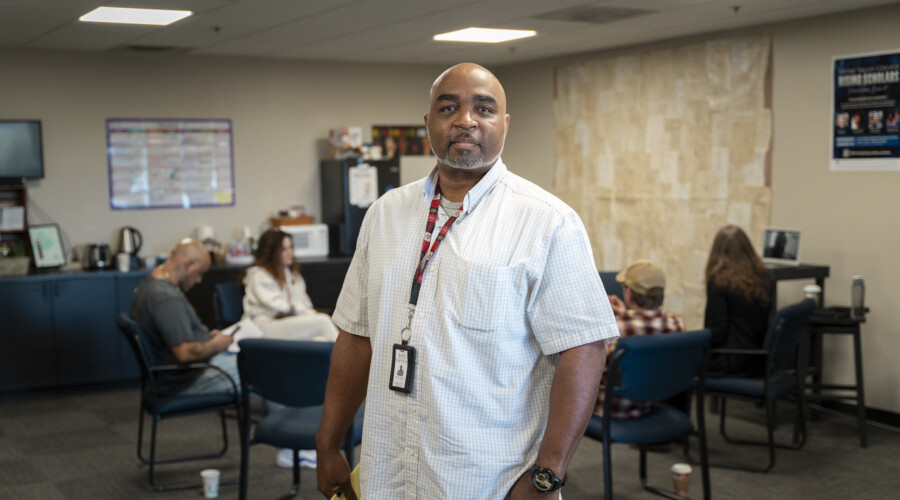

I got 16 people enrolled in City College, so they said “look we might as well give you a job.” While I still had the ankle monitor on, I became employed by the San Diego Unified School District as the outreach coordinator for formerly incarcerated students.

It felt like a seamless transition out of prison and MCRP into community college and SDSU. I was going to SDSU and Playwrights Project was also at SDSU. I stayed connected with a lot of people — it’s easy to find positive outlets when you are really changing your life.

I’ve been out of prison since January 2020.

I am a drug and alcohol counselor right now at Tradition One, a residential rehabilitation home. And I thought writing could be another form of rehabilitation. These guys who’ve had a lot of past traumas could really learn to express themselves. And Cecelia from Playwrights Project is going to bring the playwriting program to my counseling program.

My hope is that they’ll be able to talk about their experience. But it doesn’t have to be them, you know, and it can be in a setting where the machismo doesn’t allow them to share that the reason they started doing drugs or that maybe they began self-medicating because a death in the family and that just snowballed into addiction.

They often can’t really express their pain honestly in a group setting with a bunch of other men. So, I know it’s going to work. But this is going to be even more impactful.

My goal is to get them to see that their pain doesn’t go unrecognized. I come from a place where I understand that it’s not what you did, it’s what happened to you that led you to this circumstance. Most drug addiction is reactive — even if it was experimental at first — there’s some kind of past trauma that you’re trying to overcome. You’re trying to numb or dull the pain. And so, writing gives you a way to express without expressing. It is a healing process.

You can write about a painful experience, and you see others react to that pain and empathize with the characters. It lets you know that you’re not alone.

Writing in a group setting and seeing your play on stage builds camaraderie, and if you’re going through something, you’re not going through it by yourself. It’s like carrying a weight and then suddenly you’re not lifting it by yourself, the burden becomes lighter, you feel seen and understood and you realize that other people are going to similar things.”